One of Hitchcock’s most celebrated shots: it starts overlooking a party, as though standing upon a balcony, capturing the guests in their finery, though your eye is drawn immediately to Ingrid Bergman off to the right of the frame. And, soon enough, the camera descends from its height, keeping Berman to the right while pulling in tighter on her—not on her face, though, luminous as it is, but going instead towards her hand, which clutches, shakily, a key.

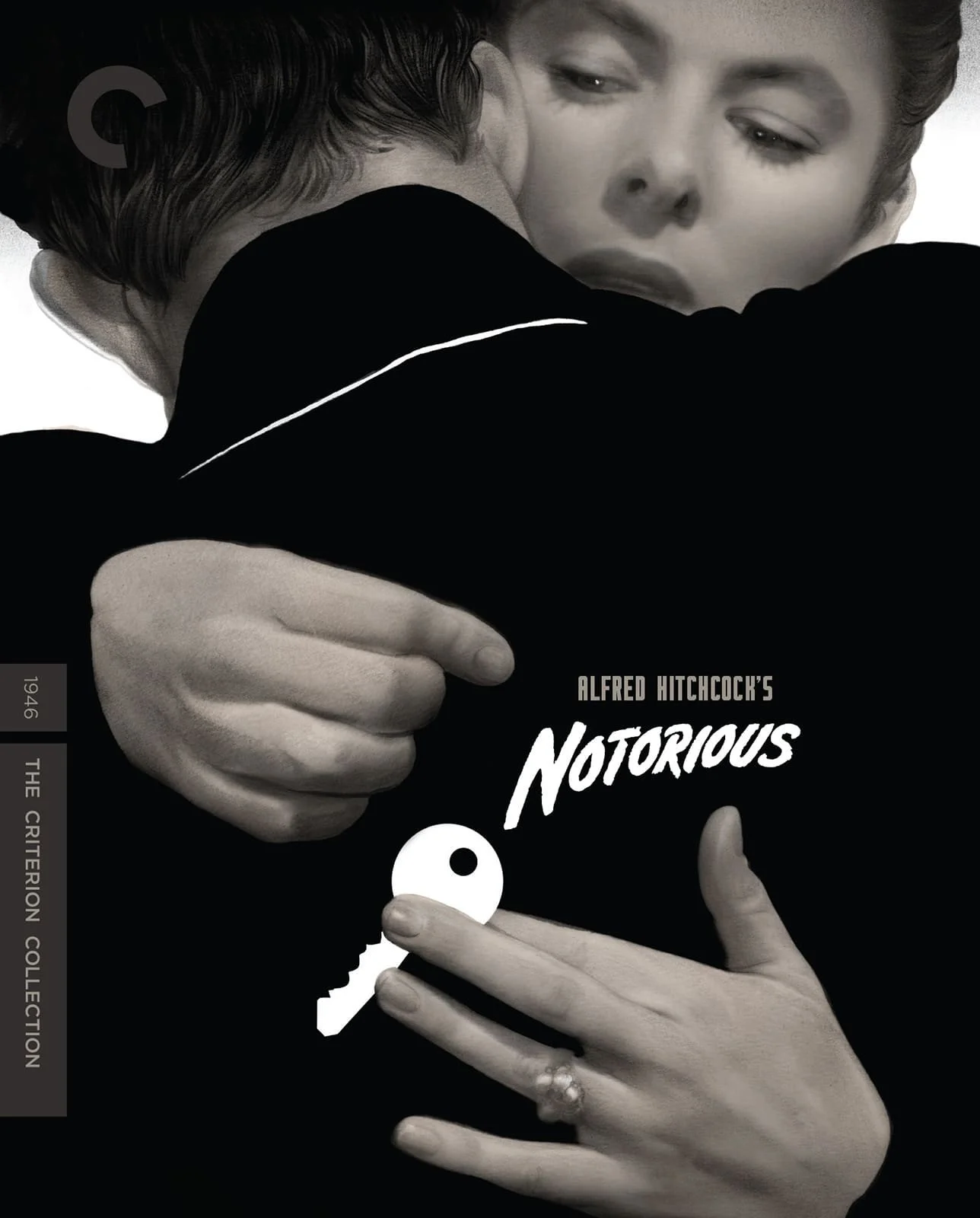

We know this Unica key is significant because Hitchcock has framed it as such: whether with an insert shot of a keyring or by highlighting it against Claude Rains’ black dinner jacket, as Bergman, in an embrace, hides it from his view. Again and again, Hitchcock puts items in the foreground: a mismatched wine bottle label. A coffee cup. And suddenly, these little things take on enormous importance—the bottle filled with uranium; the cup filled with arsenic.

When I last visited my family home in Colorado, I slept in my old room, which, for the past few years, had become my father’s room, since he could no longer able to ascend and descend the stairs to the basement to reach his room. And all over the room we shared, I found the history of myself in the paraphernalia still there: a dusty vase of dried peonies; the complete collection of Elfquest graphic novels; a tin filled with ‘collectible’ pencils from elementary school.

As for my father’s items, there was almost no trace: my brother and I had cleared out his presence shortly after his death. We thought that these would be a difficult reminder for my mother, who still used his computer to watch her chair exercise videos. We had missed things, of course—a well-worn track suit hanging up in the closet; a box of insulin needle tips in a cabinet—but these were hidden from view. I’d get to them eventually.

One night, as I was getting ready for bed, I put my glasses on the bedside dresser. I heard the clack of plastic on plastic. I had put my glasses on my father’s, which had sat at the base of the desk lamp, undisturbed for almost two years. Wire-rimmed, bifocal lenses. I should have donated them—Costco has a box in its optical department for this—but I overlooked them. Not yet, I told myself.

I tried to remember him wearing this pair but couldn’t. In those final years, he probably only used them for reading at the computer. He never wore them around the house or on those rare occasions when we would venture out for a bowl of phở. But I maybe I had simply forgotten them, the way glasses simply meld onto one’s face—our entire family has long been cursed with bad eyesight—an irreducible feature, like a nose or mouth. And it was only now, framed in the foreground, that they finally took on greater significance.