Spellbound opens with a four minute-long sequence of the musical score over a black title card that reads Overture. There are no sound cues, no images, no lead-ups to the film proper. It’s how Selznick presented his big film premieres: devoid of the incessant advertisements and previews of modern movies. But the Overture evokes something else more suited to the subject matter: the black card is like a blank screen onto which we can project our own thoughts, images, visualizations. It is, as Miklos Rozlas’ score plays, an invitation to dream.

In the past few weeks, I’ve dreamt about my father. In the most vivid one, I was watching a PBS-style documentary about his life, and even while the dream was occurring, I remember thinking to myself: That can’t be true, he never told me that. But it unspooled nonetheless: this screen within a dream, telling me all these things that I should have already known.

I used to keep a record of my dreams—it might have started in college, when I was eager to process msyelf with a freshman-level understanding of Freudian psychoanalysis. Maybe this is the process of self-discovery: by delving into our dreams, we understand our shifting selves. I remember browsing encyclopedic tomes of dream symbols and meanings: teeth falling out mean the fear of losing something valuable; arranging flowers mean a search for peace. But, in truth, there’s nothing more boring than listening to someone else talk about this weird dream he had last night.

The centerpiece of Spellbound is, of course, the dream sequence rich with Dali’s surrealism: table legs that are human; mountainous outcroppings that look like faces; wheels that appear to have melted. Interpreting the dream solves not only one mystery, but two—the subconscious as a skeleton key.

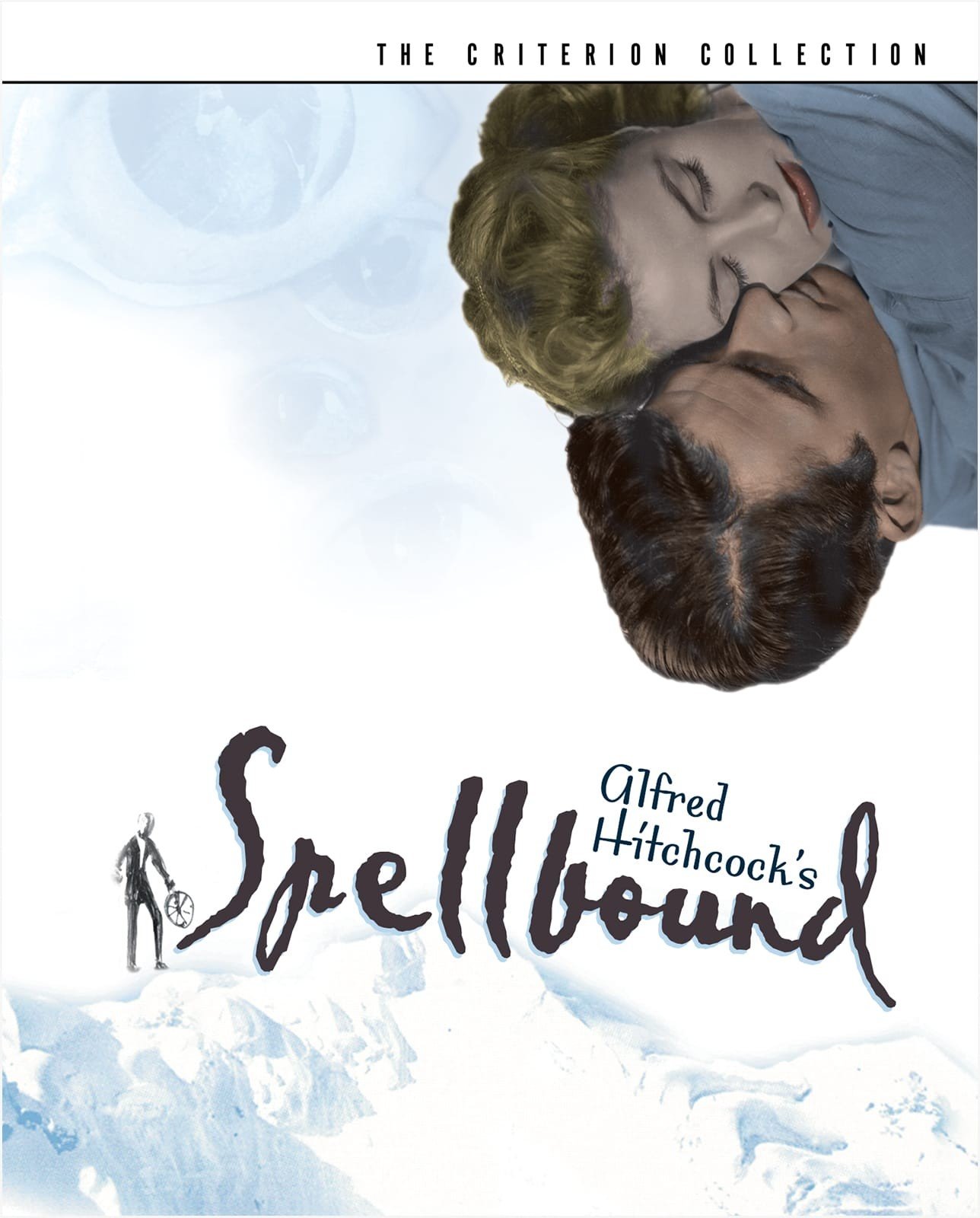

But it’s the other dream-like moment that stays with me: as Ingrid Bergman and Gregory Peck embrace for the first time, she imagines a door opening to reveal another, which itself opens to reveal another: a corridor of doors, now flung open, perhaps a too on-the-nose symbol of sexual awakening.

In the last months of his life, I tried to get to get my father to talk about his past: his experiences during the war, living in Vietnam before the war, his childhood. I wanted to understand him better, to learn about the forces that shaped him. But each time I did, he grew silent. I wonder if I should have pushed him more, but each time I asked, he turned back to the television screen in front of us. He watched almost nothing except YouTube videos of rural Vietnamese families gathering food and preparing meals, or Vietnamese pop songs from his favorite singers. Sometimes he had tears in his eyes. I put my arm around his shoulders, tried to comfort the fears and pains seeping out of him, but, in my mind, I saw a corridor of doors, each door closing shut, and locking tight.