Last night I dreamt I went to Hinkley again. It seemed to me I stood in front of the metal double doors, seconds before the first tardy bell. The doors were locked, the glass in the window crisscrossed with metal to prevent break-ins, and though I knocked, no one from the principal’s office came. The first floor classrooms stayed dark. Then, like all dreamers, I passed like a memory through the wall.

Chambers Road wound its way before the school, as it had always done, but as I advanced I noticed it had been torn up for another round of inscrutable road work. Nature had subjected it to annual cycles of Colorado snow and salt, and it had been repaved so many times that nothing remained of the original except its direction. The commercial fingers of Colfax Avenue had crept further, businesses and offices inching their way down the road like lichen, but I recognized none of them.

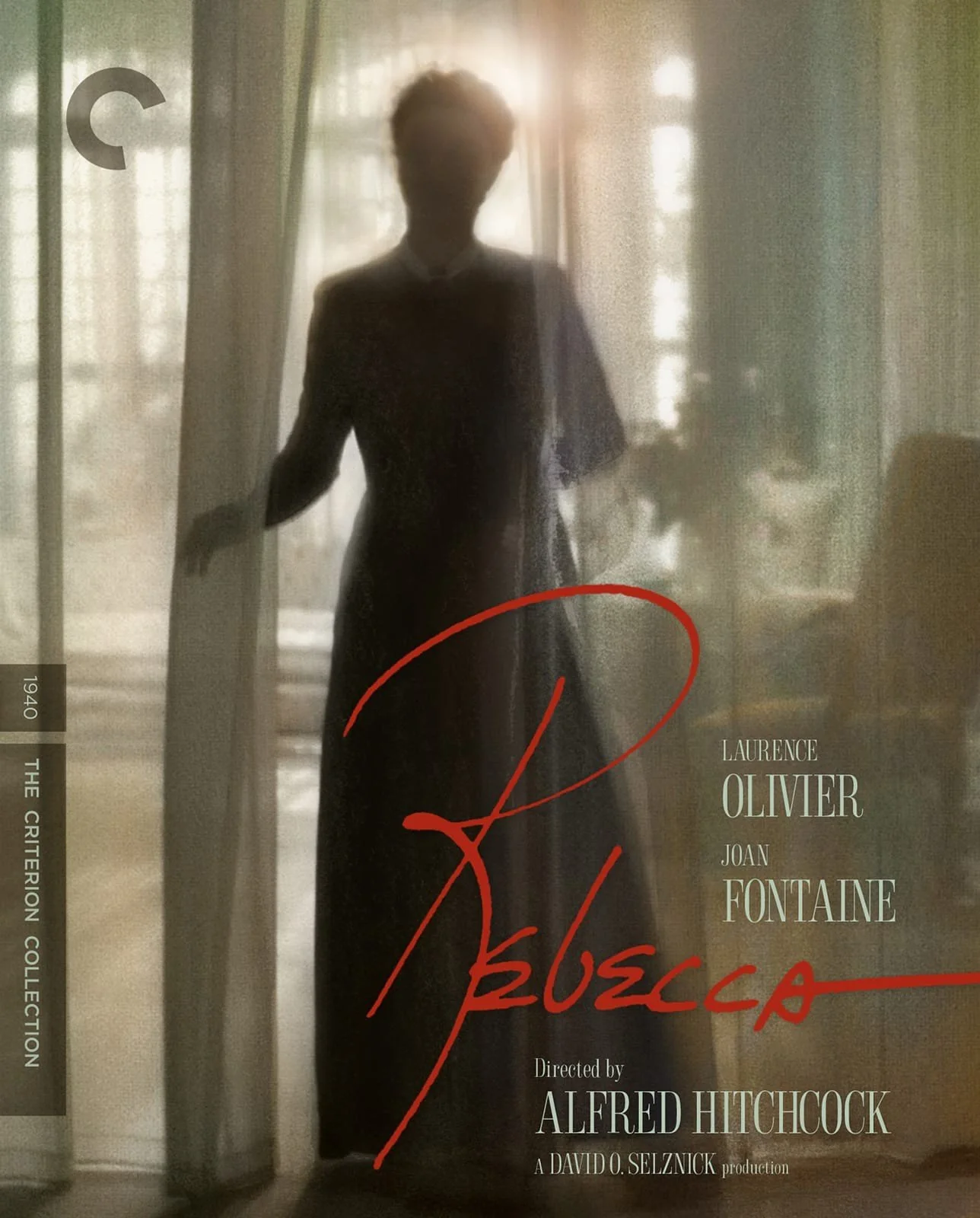

The corridors of HInkley were a tangled thread, linoleum floors cracked and stained, the halls lined with lockers that popped open as easily as a pimple. Scattered here and there were classrooms that I remembered entering: Mr. Franklin for chemistry, Mr. Otto for calculus, and Mrs. Henning for English. Mrs. Henning was a slender thing, wrinkled when I had her, a dark bob and glasses. She taught the classics, of course, but did not balk when a klatsch of girls in the back had taken a liking to E.M. Forester. She did not bat and eye when I slipped out a paperback copy of Rebecca, gifted to me by my sister, the ornate prose falling like gauzy veils across my eyes.

There was Hinkley, our Hinkley, stoic and industrial as it had always been, the swimming pool enclosed in gray glass such that you had to peer beyond your reflection in order to see the water, as though watching through cataract-laden eyes. Time could not tilt the cinderblock walls, beige and bland, nor the brick façade that made it appear more impressive, a minor jewel in the crown of the Aurora Public Schools.

Memories can play odd tricks upon the fancy, even upon a dreamer’s fancy. As I stood there, contemplative, I could swear that the school was not paused for summer recess, but still thrummed with students streaming in and out.

They were memories that cannot hurt, for I knew I was dreaming. In reality, I lay many hundred miles away in Delaware, and would wake by the scratching of a cat who wanted to get under the covers but then changed her mind at the last second. And now, it was my turn to convince students to read and write, a long afternoon no doubt, fraught with anxiety that carried from my dream and into my waking life. But I would not talk of Hinkley, I would not tell my dream. For Hinkley was mine no longer. Hinkley was no more.